3D product experiences can be useful on ecommerce sites. They are not needed on every site (yet), but just like zooming in on a product image can be useful, so can a 3D representation of a product. You can look at a product from all angles, possibly animating it to show it in use (functional appeal), or show the product in engaging environments (emotional appeal). I expect the need for 3D models of products will continue to increase over time as XR and “Spatial Computing” experiences become more common, but I suspect site-specific custom experiences may be a bigger short-term driver.

What? Aren’t I excited about 3D on the web? Well, yes, kind of. The reality is 3D assets are still expensive to create, and 3D assets are larger than their 2D counterparts. So use them if they solve a problem on your site, otherwise but the reality is not everyone needs them. (Yes, I am also good at sucking the life out of parties!)

Use Cases

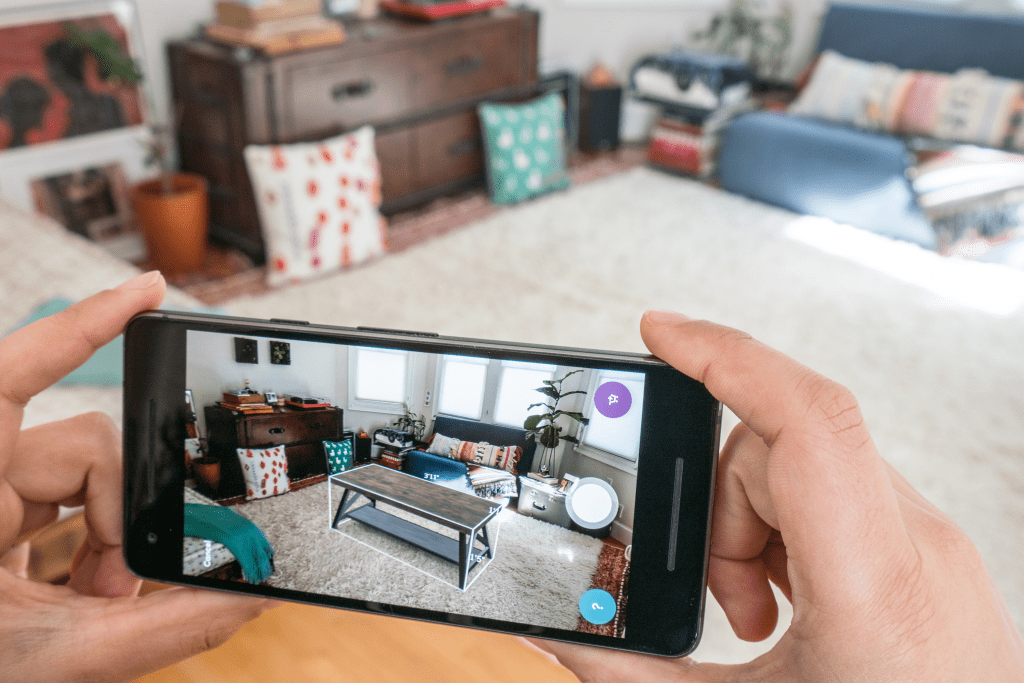

What are some different ways 3D assets can be useful on a web page? The simplest is to view single products. A bit nicer can be single products with a background 3D environment, or an AR experience where you can get a feel of what furniture will look like in your environment before purchase.

Wayfair AR app

More interesting is when you start combining models in a single scene. I will use the example of interior design in this blog. Pick from a library of furniture you have for sale and add it to a room to see what combinations may look good. The shopper can adjust viewing angles, lighting, colors, material variations and more.

Room model by Christy Shu on Sketchfab rendered in NVIDIA Omniverse

It can be used to develop more engaging experiences, especially when combined with hardware such as the Apple Vision Pro.

OpenUSD is powerful and flexible enough to allow separation of responsibilities between teams. This is a key benefit making it attractive to larger organizations.

Status Quo

Most 3D experiences on the web today are glTF based. glTF is a JSON file that references external images files. There is also GLB, a binary representation that bundles the glTF JSON and external image files into a single downloadable ZIP. glTF and GLB are natively supported by WebGL, making them good choices for the web. I will focus on GLB from now on since GLB is usually more convenient – you can download a complete, self contained 3D model with a single URL.

While GLB files are good for representing 3D models, they are not designed for creating a complete scene including multiple other models. (You can create a complex scene in a single GLB file, but you cannot compose multiple external GLB files into a scene.) Three.js is a JavaScript library that adds support for scene composition, Babylon.js is another. Using these libraries you can build up a scene from multiple GLB files, such as for an interior decorating website: let the user pick a base room then start adding items of furniture from a catalog.

There is another format however, OpenUSD, that has been gaining traction. Universal Scene Description (USD) originated at Pixar, designed to support the creation of high quality feature length animated movies. It is a rich format with many features to support complex 3D workflows and pipelines. The Alliance for OpenUSD (AOUSD) is standardizing and expanding the scope of USD. It was recently founded by Pixar, Adobe, Apple, Autodesk, and NVIDIA, but already contains over 20 general members.

I am seeing OpenUSD more and more frequently appearing as a supported file format of tools and websites related to 3D models. The Apple Vision Pro adoption of OpenUSD for its 3D models has not hurt either!

OpenUSD internally uses a hierarchical representation similar to XML and JSON, where “prims” (primitive elements or nodes) can have properties, with a range of types suitable for 3D models, and children prims. Files, prims, and properties can all also have machine readable metadata. There is a textual encoding, USDA, as well as a binary encoding, USDC, which is more efficient for binary data such as meshes. There is also USDZ which, similar to GLB, packages USD files with supporting external image files into a ZIP file in a standard way.

OpenUSD can be used to develop interactive experiences in web pages, for AR/VR/XR devices, as well as more traditional video files.

To learn more about OpenUSD, NVIDIA published an introductory video series.

Do you need to choose between GLB and OpenUSD? Not necessarily. There are efforts to improve the ability to import GLB files directly into an OpenUSD scene. This would let you use OpenUSD to compose scenes from multiple model files without having to convert them to OpenUSD first.

In this post I am going to focus on the potential benefits of OpenUSD for scene composition in ecommerce contexts. There are challenges for OpenUSD adoption on the web so I don’t think it is always a clear choice over the more traditional methods of GLB with a JavaScript library for scene composition. But there are benefits to OpenUSD and I think it is worth anyone considering building 3D applications on the web to understand the pros and cons.

OpenUSD for Marketing and Advertising

Why am I writing this post now? This week’s stream from the NVIDIA Omniverse team was on the use of OpenUSD for creating marketing material. The full livestream started with the NVIDIA team talking about technical aspects and tools they have been creating, with the second half covering work by WPP in creating marketing content using OpenUSD.

A 5 minute video is also available here

I would not be surprised if there were more details released at SIGGRAPH in Denver (July 28 to August 1). If you are going to SIGGRAPH 2024, there are several events that might interest you. July 29 Jensen Huang (NVIDIA CEO) will have a fireside chat with Lauren Goode from WIRED (he has frequently promoted Omniverse and OpenUSD in his keynotes), July 30 is OpenUSD day including an OpenUSD developer meetup, and July 31 has OpenUSD training labs.

In the live stream, WPP talked about how they use OpenUSD to render inspirational car videos. Watch the video for details, but they make the case why it saved them money. Rather than shoot one vehicle driving down the road, they can now digitize environments allowing them to update videos to show the current year’s car model with selected coloring and options. They don’t have to reshoot a whole video live on set. The live stream even shows how they use a robotic “dog” from Boston Dynamics to help perform LIDAR scans of whole stretches of road, automatically removing passing vehicles. Pretty cool!

While ecommerce is not the primary focus of Omniverse (it focuses more on industrial 3D applications such as digital twins, robotics, and AI), they have produced a number of demos directly relevant to product configuration. For example, there is a whole YouTube series on “data driven configurators”.

Why are cars featured so frequently in such experiences? I suspect it’s because 3D experiences are still relatively expensive to create, meaning good ROI is easier with common but expensive products. Houses and cars make up the two most common and expensive purchases for most people, so it’s a logical place to start. And as an added bonus, there are good CAD models for cars. I don’t think it will end there however.

Getting Technical

Let’s take a quick dive into OpenUSD for use in ecommerce product models and scenes. I start with some basic terminology, but I jump into some deep technical details later.

In OpenUSD, the Stage is where a scene is loaded. A scene is commonly composed from multiple USD files. In OpenUSD, even models are frequently broken down into multiple files that may be combined in different ways. There is no requirement for this, but OpenUSD was originally designed for use by teams at Pixar with different responsibilities. Separating files meant each team had clear ownership of its set of files, avoiding editing conflicts, but all teams could see the result of combining all those files at any time.

A common concept that you often hear with OpenUSD is layers. Just like in Photoshop, you can build up your creation in layers. Higher layers override lower layers. This allows a “non-destructive editing workflow”. Put simply, you can add a new layer and make changes that override what is in lower layers without modifying the lower layer file contents. This is what makes OpenUSD so useful with teams. For example, if a marketing team overrides the paint job on a car, then the engineering team ships an updated version of the base car model, the marketing team’s changes will (typically) be preserved. The marketing file with local changes references the engineering provided car model file. This approach can be extremely valuable in reusing assets across a range of use cases.

OpenUSD for ecommerce

A big decision with OpenUSD is how to organize your assets and workflows to manage/update the files. For example, I have already mentioned that OpenUSD maintains rich machine readable metadata on prims. There is “kind” metadata for prims with values including “assembly”, “group”, “component”, and “subcomponent”. Prims that represent a model, such as a product to sell, would generally have “kind” set to “component”. Prims inside would have a “kind” of “subcomponent”. Above components, scenes are created from “assemblies” and “groups”. Assemblies in OpenUSD contain references to components including where the place them in 3D space. This metadata can be useful when developing applications. Clicking on a piece of furniture in a scene can now be made to select a chair (a “component”) rather than just the leg of a chair (a “subcomponent”). You just climb up the hierarchy of prims until the “component” prim is reached. The application can also make decisions such as to save scene changes in the assembly file and never modify components. These rules are not enforced by OpenUSD – it makes it possible for applications to define their own rules based on the rich OpenUSD data model.

OpenUSD also natively supports “variant sets” and “variants”. There was one sofa I came across that had 76,500 possible variations (different materials, different leg colors, different nails, different stitching, different padding, different arm designs, etc.). The sofa in question had 9 independent aspects that could be varied which led to the explosion of variations. In OpenUSD, they can be encoded in 9 variant sets. Applications using the model can then provide drop down lists to select which variant to use for each set. The application does not need to understand how the sofa model works internally – it just selects variant names per variant set listed.

Variant sets even get their own video series:

Relationship Forwarding

Returning to the interior design use case, variant sets can be a useful way for someone creating a model to make all of the options for a product available to the programmer developing the website. But what if the set of materials or colors is not known? For example, an upholsterer has a huge selection of materials they can use to recover a chair. In this case a variant set will not be useful as it is not the chair defining the materials that can be used. In this case, how to standardize furniture models to make it easy for an application to change a material on a piece of furniture without the application developer having to understand how the model was created?

I was wondering about how best to do this in OpenUSD when I came across a feature called “relationship forwarding”. Each prim has a series of properties that are broken down into attributes (strings, numbers, arrays) and relationships (arcs to other prims or assets). OpenUSD allows schemas to be defined, but you can also just put naming conventions in place. Binding of materials to meshes are typically performed using relationships.

If you have a component (like a piece of furniture), normally each mesh in the component identifies the material it wants to use on that mesh. But if the component wants to reference a single material multiple times, you can set up relationship forwarding. Consider the following “chair.usda” file. Instead of binding “seat” and “backrest” to “/chair/defaultMaterial”, they bind to the “clothMaterial” property of “chair”. “clothMaterial” then refers to the material “/chair/defaultMaterial”. Updating “clothMaterial” will then update both meshes automatically.

#usda 1.0

(

defaultPrim = "/chair"

)

def Xform "chair" ( kind = "component" ) {

relationship clothMaterial = </chair/defaultMaterial>

def Material "defaultMaterial" ( kind = "subcomponent" ) {

...

}

def Mesh "seat" ( kind = "subcomponent" ) {

...

relationship material:binding = </chair.clothMaterial>

...

}

def Mesh "backrest" ( kind = "subcomponent" ) {

...

relationship material:binding = </chair.clothMaterial>

...

}

}

By itself this can be useful, but normally I would not bother doing it. Where it becomes powerful is if you start thinking about a component having a standard “interface” for assemblies wanting to use the chair. In your project you could set up a convention that any component that represents a piece of furniture where the material can be changed will define a root level “defaultMaterial” property. Applications assembling a scene can look for the existence of that property and then let the user choose the material. The application does not need to hunt around inside the component trying to find possible material references. It keeps the “API” between the component and users of the component clean.

Here is an example stage.usda file that adds multiple references to the chair.usda file, where the clothMaterial property of the root prim is overridden in different ways per chair.

#usda 1.0

(

defaultPrim = "World"

)

def Xform "World" ( kind = "assembly" ) {

def "chair1" ( references = @./chair.usda@ ) {

relationship clothMaterial = </World/myLocalMaterial1>

}

def "chair2" ( references = @./chair.usda@ ) {

relationship clothMaterial = </World/myLocalMaterial2>

}

def Material "myLocalMaterial1" {

...

}

def Material "myLocalMaterial2" {

...

}

}

Thus by introducing simple conventions, references to component asset files can easily override materials in a model in a consistent way.

“Relationship forwarding” is one example of a number of advanced features in OpenUSD. Another way is to add metadata to prims for other code to later use. For example, instead of relationship forwarding, the prim could have metadata added listing the paths of all material bindings in the hierarchy that need updating to change the cloth. Application code changing a material would check the metadata first, then iterate over all the listed prims.

OpenUSD is powerful and flexible enough to allow separation of responsibilities between teams. This is a key benefit making it attractive to larger organizations.

Web Application Development

I have previously blogged on rendering products in web pages with Omniverse Cloud. In that post it talks about running an instance of Omniverse in the cloud for performing rendering, then having a React frontend sending JSON messages to the instance in the cloud. The frontend React code and the backend Omniverse application have to agree on the supported messages, but the frontend code never has to manipulate OpenUSD directly.

There is another approach however, which is to manipulate OpenUSD stages directly in the browser.

A Web Assembly build of the OpenUSD SDK has been built, making the full OpenUSD APIs available in a web browser. The OpenUSD SDK is written in C++ with Python bindings available. The WASM build is unfortunately relatively large, and there were some challenges in the port due to multi-threading support in the C++ code base.

Personally, I like manipulating and rendering OpenUSD in the browser for interactive experiences. You don’t need a dedicated cloud server running per user with a video stream from the cloud to the user’s device, and latency is reduced. Rendering in a web browser currently is lower quality although things have been improving. So for now I like keeping rendering on a cloud server for final high quality renders, or for fly-through movies. They can be kicked off as a background job (also allowing the render server to be shared across users on the site, keeping costs down).

So how to structure a web application manipulating an OpenUSD scene? I was recently kicking ideas around with the folks from Cloud Zeta (a startup focusing on hosting 3D assets such as OpenUSD files). They have a build of the OpenUSD library in WASM with a number of rendering and multi-threading optimizations.

Their current preferred approach for web development is to maintain all 3D state in the 3D OpenUSD stage. Want to find all pieces of furniture in a scene? Fetch the children of “/World” via OpenUSD API calls and look for prims with “kind = component” in the current stage. Want to work out the current color of a material? Fetch it from a property of the material. Want a React color picker to update the color of a chair? Use useEffect() to watch for UI state changes and then call the OpenUSD function to change the property when the color value changes. This allows most of the application to still be written as normal React code, with occasional calls to the OpenUSD library.

One missing part however is the ability to trigger React state updates if the stage is modified. A modification might be as simple as “stage is now loaded.” More advanced cases is where there are concurrent people modifying the same stage. Maybe you have a team of interior designers working on the same 3D scene.

What Cloud Zeta have been exploring is the approach of registering “listeners” to watch for updates to specified prims in the sage. For example, watch for new children to be added under a named prim. If a new child is added (say a new piece of furniture), React is informed of the change and can, err, react (make OpenUSD API calls to check the current state).

The Cloud Zeta folks describe the mental model as “treat the OpenUSD stage like a database”. Read from OpenUSD to get authoritative data, add listeners for particular updates you want to be informed of immediately, and submit updates when the React web interface needs to change state. This approach is not specific to React – it is applicable to many existing web development frameworks.

Wrapping Up

Not all applications require complex 3D scenes. But when 3D scenes are required (such as for an interior design website), OpenUSD can be a useful format that allows both complex scene assembly in the browser, but also high quality offline renders.

The decision between OpenUSD and more traditional glTF/GLB formats is not always a simple one. For simple applications, there may not be a reason to move away from glTF/GLB. glTF/GLB is generally more efficient on the web today. OpenUSD however generally has richer data modelling capabilities and becomes more interesting when you have multiple teams involved. It is more complex, but that complexity can make it easier to divide work between teams. For Pixar, this was originally different teams of artists (modelers, riggers, animators, lighting, etc.). But this power is proving its value in other businesses as well as the use of 3D models starts crossing internal team boundaries between ecommerce product data management, engineering and marketing teams.

The other unknown is the impact of WebGPU. Will it provide an opportunity to significantly increase the quality of rendering directly in the browser? And will mobile phones be able to cope?

But I do believe the benefits of OpenUSD are increasing as 3D assets are getting used by more teams within an organization. I don’t think this growth will be rapid, but it is coming. Hopefully this blog post helped raised understanding of the potential benefits of OpenUSD, at least for more advanced ecommerce applications.

Got questions about OpenUSD? Feel free to leave a comment and I will do my best to get back to you, or feel free to reach out to @Ordinary Alan on the NVIDIA Omniverse Discord server.