Film and TV production has a rich history and culture. Personally I am trying to use AI to speed up the creation of a simple computer animated series: insert a screenplay and out the other end comes a simple animated video.

I have not been to film school, but I do think there is value in understanding industry practices that have proven to be effective. This is my quick summary of techniques for creating a story that is eventually converted into video media.

Industry Conventions

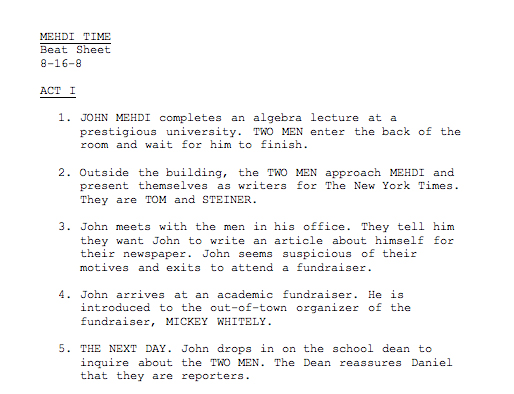

Beat sheet: Captures each significant moment of the story as a beat, with a sentence. Beats typically include who, where, and the conflict/tension of the beat. (No conflict? Maybe delete the beat!) A good story has cause an effect between beats so the audience can follow the flow. Some software seems to use “cards” as a way to limit the amount of text that can be written.

Is it always one sentence? No. The idea of a beat sheet is to provide tools and techniques to help the writer, not restrict them. So do whatever works for you. Not every one creates beat sheets, but they appeal to me as they provide a high level overview of structure. That is true of everything listed here. These are tools found to be useful by creatives, not strict rules that must be followed rigidly.

Example beat sheet from https://eyesondeck.typepad.com/scriptfaze/2010/12/the-beat-sheet.html

A full feature film (say 120 minutes) often has 70 to 90 beats.

Outline: Goes deeper than a beat sheet with narrative story for each beat. There is no dialog, but it fleshes out the story – the wants and needs of the characters, and adds a bit more flesh to the beats. Some people use beats, others outlines, or both.

Treatment: A treatment of a story offers different perspectives of a story. In my reading it almost felt like a sales pitch for the story. Useful to get investors interested. You might have sections such as

- The title and author

- A logline: a powerful one or two sentence description.

- Concept: A few paragraphs of text going into greater detail about the story.

- Theme(s): A description of major themes during the story.

- Plot points: A list of interesting plot highlights.

- Characters: A profile of different characters including background or mannerisms.

- Locations: Places where things happen.

- Synopsis/summaries of the three acts that make up most films.

Treatments don’t have dialog. They are to give people an understanding of the goals of the story and why it will be interesting to people.

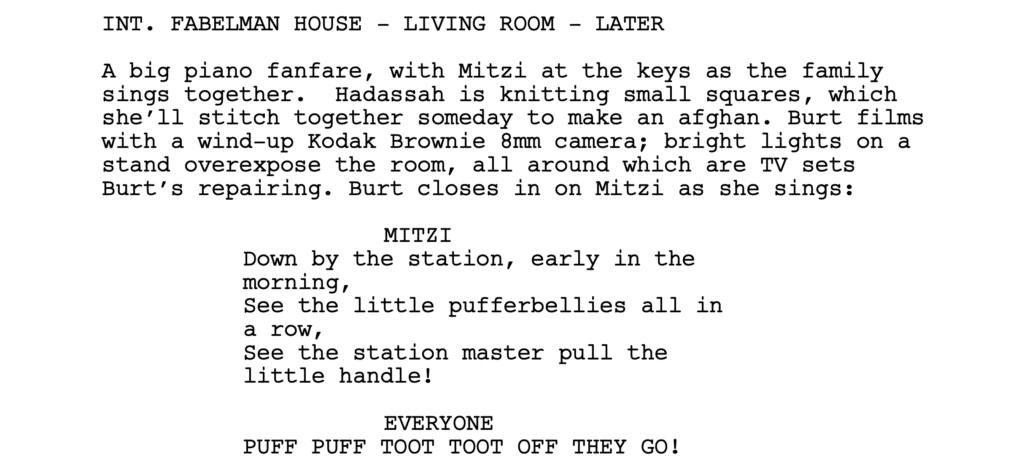

Screenplay: Next comes the screenplay. The beats flesh out into scenes (not always one-to-one). There are scene headings with action and dialog per scene. Special effects may get a mention. There is often a question of what to leave out of a screenplay. For example, include dialog but actors can improvise. Describe important aspects, but often actors don’t want the screenplay to be over prescriptive. Same for camera movements – the director and cinematographer don’t’ need to be told what to do. Include important points, but don’t describe every camera shot. (One quote said each paragraph of a screenplay will probably turn into a camera shot, but don’t overwhelm the reading with lots of technical details).

There are other conventions like what to capitalize. The first mention of a character or prop in a scene may be capitalized, but maybe not every instance in a scene. It gets distracting. The first occurrence is capitalized to emphasize who is in the scene.

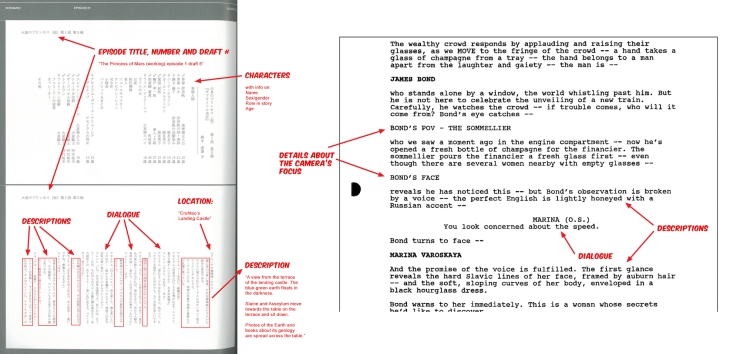

The most common structural units of a screenplay are:

- Scene headings, starting with “INT.” for interior scenes or “EXT.” for exterior scenes, then followed by a location name and time of day

- Action instructions in paragraphs of text.

- Character names (in all caps) preceding dialog. Standard suffixes include (V.O.) for a voice over by a character, (O.S.) for “offscreen” if you can hear a character but not see them, and (CONT’d) if a character continues to talk.

- After a character name, an optional line in parentheses can come to indicate the mood the dialog should be spoken with.

- Then comes the dialog itself.

These different units have different indentation standards.

Example from https://www.scriptreaderpro.com/best-screenplays-to-read/

Storyboards: Storyboards can be useful after the screenplay has been written to give a feeling of the film. Each board has a single static image. Start exploring camera angles and transitions, but also colors and lighting which impact the mood of a scene. With storyboards + voice acting you can start “watching” the film, which can help getting a feeling of pacing.

In addition to storyboards, color/mood boards may be created to give an overall visual feel for a production.

Image from https://www.animationmentor.com/blog/lighting-and-color-in-animation-films/

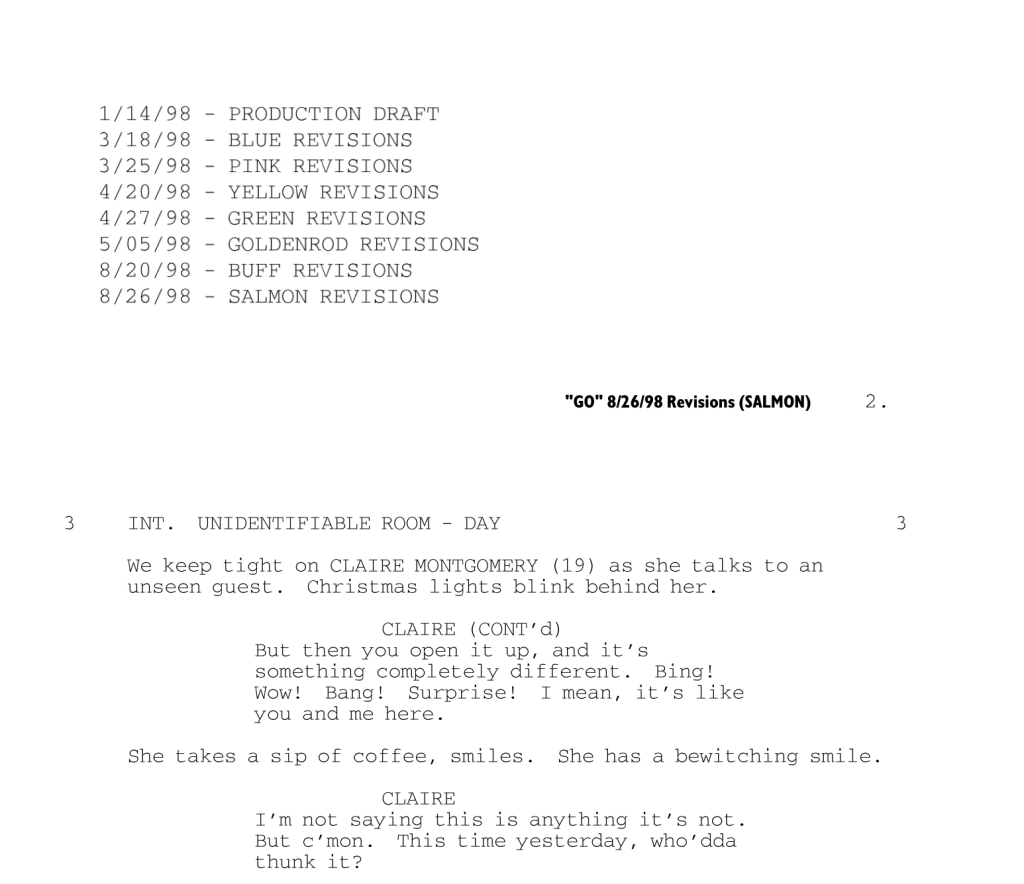

Shooting scripts: The screenplay is taken and annotated to incorporate shooting instructions. This includes the proposed camera shots and other technical details to assist with filming. The shooting script often goes through multiple revisions at this time, and there are conventions about the color of paper to use for each version of each page, to make sure everyone is working to the same version of the shooting script.

Shooting scripts have the following conventions added over a screenplay:

- Scene numbers are turned on. A screenplay does not need scene numbers to be locked down, but when you start production that is the time you want stable numbers. If you need to add a new scene, use “3A” or similar rather than renumbering existing scenes.

- Page numbers also tend to be locked down at this time. If the contents of a page needs revising so it no longer fits on one page, then overflow onto a newly inserted page 5A so a new version of the page can be printed and slotted into the script without renumber of the rest of the script.

- Capitalization in a shooting script is more common. Every reference to a character or prop may be capitalized for clarity. Smooth reading is no longer a priority, but rather technical clarity. The purpose of a shooting script is clarity for all team members producing the movie.

- In addition to the main structural units above, there may be more camera instructions. Shooting directions may be in a separate paragraph per shot in all caps.

One person used “production draft” for a shooting script. Many published scripts may be shooting scripts rather than screenplays.

Sample from https://www.studiobinder.com/blog/shooting-script-example/.

Shot list: A shot list can then be developed from the shooting script. When filming starts, the shots do not have to be recorded in the order of the screenplay. If there are two characters talking to each other in a scene, lighting may need to be set up for each character. So it may be the first character has all their lines of dialog shot (often with multiple takes), then the camera and lighting is set up to take the shots of the second character. This reduces total effort. If there are multiple scenes at the same location, it is even possible to take all of the shots at a location before moving on to the next location. So the shot list is very important when filming in the physical world.

Shot lists may get very specific about the camera shots that will be taken. Examples from Studio Binder include:

- Shot number.

- Shot size

- Close-up shots: Close-up, Medium Close-up, Extreme Close-up, Wide Close-up

- Medium shots: Medium Shot, Close Shot, Medium Close Shot,

- Long shots: Wide Shot, Extreme Wide Shot, Full Shot, Medium Full Shot, Long Shot, Extreme Long Shot

- Shot Type

- Camera Height: eye level, low angle, high angle, overhead, shoulder level, hip level, knee level, ground level

- Dutch Angle: Dutch (left), Dutch (right)

- Framing: Single, Two Shot, Three Shot, Over-the-shoulder, Over-the-hip, Point of View

- Focus/DOF: Rack focus, shallow focus, deep focus, tilt-shift, zoom.

- Movement: static, pan, tilt, swish pan, swish tilt, tracking

- Equipment:

- Mechanism: Sticks, hand held, gimbal, slider, jib, drone, dolly, Steadicam, crane, pedestal

- Direction: Forward, backward, left, right, up, down

- Tracks: Straight, Circular

- For example, a “downward pedestal shot”

Lined Script: Once shooting starts, a lined script may be created which is where each recorded take is drawn as a line over a screenplay to indicate the length of the recorded segment. The squiggly line shows who’s face is visible, which is useful for the video editor later when picking which takes to use in the final production.

Image from https://editstock.com/blogs/all/how-to-read-a-lined-script

Extra Ordinary

I have been working on a cartoon series called Extra Ordinary. I have never got very far with production as I get distracted by the technology too much (I am a programmer at heart, and this is a hobby when I have spare time). My utopia is to produce a YouTube series where I can release an episode every week. To help with this goal, I need lots of automation to help me. I also am planning for short episodes (3 to 5 minutes) as its not all automated (e.g. video editing). So I was interested in how Japanese Anime series are put together.

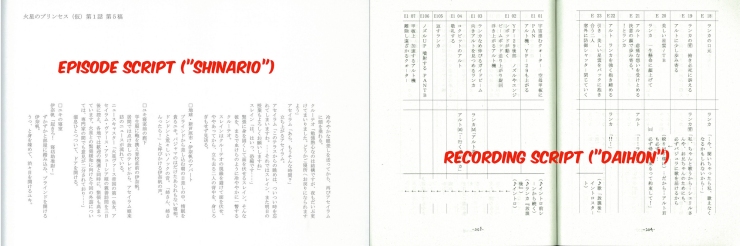

I captured some rough notes a few years back, but there are other interesting posts around. For example https://karice.wordpress.com/2016/04/03/p501/ gives a glimpse into the difference between how the US and Japanese cartoon series are often created.

In the US:

- Breaking the Story: Basic outline of the whole season (show) including theme and main character arcs.

- Premise: In-depth summary per episode.

- Outline (optional): Go further into depth for an episode which is sent to the script writer for the episode.

- Record Draft: Script for voice actors.

Due to costs, many animations are then sent overseas at this stage to be turned into animations. They match the visual to the audio play they have (the output of the Record Draft).

In Japan, it seems more common that the voice is added after animation, and all the voice actors are in the room together. It feels also like each studio comes up with an approach that works for them. It is not less structured, it is just there may be more variance between organizations as to what their structure is.

Examples from https://wavemotioncannon.com/2017/07/05/anime-pre-production-from-story-to-script/

For myself my “process” is:

- Plan a show. What are the goals, the characters, themes. What is the message I want to get across and what are the character personalities and growth arcs in order to get the message across.

- Plan a first series. What are the main plot lines, story arcs. I might have ideas I like but don’t fit into the first series, so I save them up in case there is enough interest for a second series.

- Plan episode arcs. I group a series of episodes in my mind. You can chop and change between arcs, but I think it is more satisfying for the audience to close out one arc before starting the next. They may be several character growth arcs during the episode arc, but not all characters grow each time. There can also be subplots that simmer away in the background across arcs, building background and teasing for a later arc. But I think hierarchical. I think about the growth of characters at the start and end of the arc as I believe character development is what makes stories interesting.

- Plan an episode. These is where beat boards for a script come in for me. But it should link back to the episode arc goals for cross checking. Did I mess up some dependency during rewriting?

Ordinary Animator

I am trying to decide what stages of the above make most sense for my support tool I am building, OrdinaryAnimator.com. I want to take written text and assemble a series of video clips to be edited using video editing software into the final video. My goal is to output a series of video clips, either one per scene or one per shot which can be trimmed, color corrected, background music added, etc. in video editing software.

The Lined Script for example is interesting – should I record all cameras for the full duration of a scene and use features like Multi-Cam support in Premier Pro to allow the video editor to choose the camera during video editing. I might generate the default recommended video from the shooting script, but allow the editor to tweak it outside my tool.

Another consideration for myself is whether to provide tools for writing a screenplay, or rely on other existing tools. For example, Final Draft is commonly used software that obeys the industry standards for formatting screenplays. A .fdx file is a Final Draft XML file. There are other tools like WritersDuet.com that can also export to .fdx files. I can import .fdx files, but should I allow them to be edited as well?

Of the above stages of screenwriting, I think a “Shooting Script” is the closest to my needs. I want locked down scene numbers for when I start creating video clip files. I also would like camera directions (although I was expecting more camera instructions in shooting scripts online – I may need to explore using AI to recommend adding more camera shots).

I may also want additional detail added for other purposes. For example, if I want to use generative AI for creating background images for scenes, I may want the shooting script to include “generative AI prompts” for the first occurrence of a location.

Conclusions

I have not made a final decision on what to support directly in OrdinaryAnimator.com for editing screenplays. There are some great open source around for editing documents directly on a page (such as Quill), but the reality may be that writers want a tool that supports all of the previous stages from beats, to outlines, to treatments, to screenplays, to storyboards, and finally to shooting scripts. Creating my own tool for all of the previous stages may be challenging.

On the positive side, attempting to collect all the other text for a video to be rendered has the advantage of having more information to provide to the AI when it analyzes shooting directions.